The Google File System Design Condensed

The Google File System paper was a lot of fun to read. This is what I got out of it while trying to figure out its main design points, parts summarized from the paper.

- A GFS cluster consists of a single master, multiple chunk servers and is accessed by multiple clients.

- Files are divided into fixed-size chunks.

- Each chunk is identified by an immutable and globally unique 64 bit chunk handle assigned by the master at the time of chunk creation.

The Master Server

- The master maintains all file system metadata. This includes the mapping from files to chunks, and the current locations of chunks.

- The master does not keep a persistent record of which chunkservers have a replica of a given chunk. It simply polls chunkservers for that information.

- It also controls system-wide activities such as chunklease management, garbage collection of orphaned chunks, and chunk migration between chunkservers.

- The master periodically communicates with each chunkserver in heartbeat messages to give it instructions and collect its state.

Why is the master not a bottleneck though?

Clients never read and write file data through the master. Instead, a client asks the master which chunkservers it should contact. It can ask for the addresses for as many chunk servers as it wants. It caches this information for a limited time, and only contacts the master again when it needs a new file or when the cached data has expired.

Why is the chunk size so large? (64MB)

- Client won’t need to ask the master for chunk location (Wouldn’t work as well if it was random access of different files, but its mostly sequential read writes)

- Because of the above, lesser network overhead with a a TCP connection to the chunkserver

- Lesser metadata stored on master

- Problems with such a large chunk space?

- Space wasted due to fragmentation - Lazy space allocation to prevent wasting space as much

- Small files might have just the one chunk, so they have to have a higher replication factor so that one server doesn’t become a hotspot

Metadata

- The operation log contains a historical record of critical metadata changes

- The master stores three major types of metadata: the file and chunk namespaces, the mapping from files to chunks, and the locations of each chunk’s replicas. All metadata is kept in the master’s memory. Less than 64 bytes of metadata for each 64 MB chunk.

- Since the operation log is critical, we must store it reliably and not make changes visible to clients until metadata changes are made persistent

Consistency

- The GFS follows the relaxed consistency model.

- After a successful series of writes, the GFS guarantees that the data will be consistent by

- Using chunk version numbers (stored by the master when granting leases) to detect stale chunks, which are updated asap and not handed to clients

- Master leases to a chunkserver called the primary, which decides the order in which the writes and appends, hereafter called mutations, will be applied to the chunk

- By applying the series of write in the same order on all replicas

- Note: Works as well as it does because the applications mostly append and not randomly write

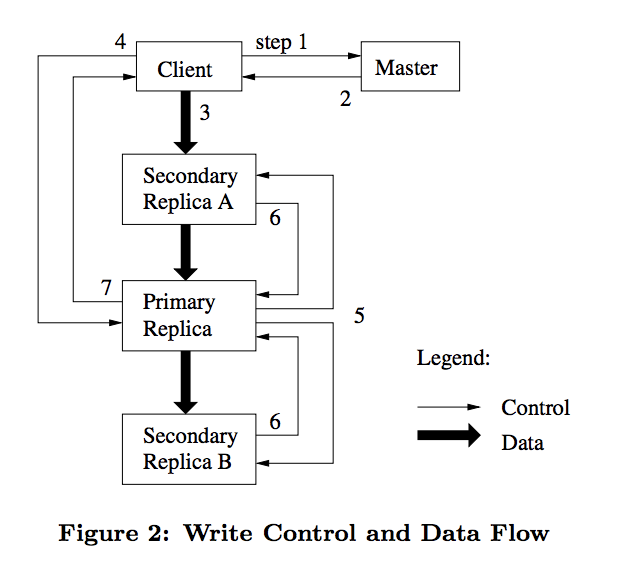

The flow

- (Steps 1 & 2) The client asks the master for the primary and the secondary chunservers. If there is no primary, the master will grant primary status to one.

- (Step 3) The client then sends data to all the chuckservers.To fully utilize each machine’s network bandwidth, the data is pushed linearly along a chain of chunkservers rather than distributed in some other topology (e.g., tree). Thus, each machine’s full outbound bandwidth is used to transfer the data as fast as possible rather than divided among multiple recipients.

- (Step 4) Once all confirm the receipt of the data, the client sends a write request to the primary.

- (Step 5) The primary numbers all the mutations and applies them in that order to the chunk. Once its writes have finished, it sends the order to the rest of the servers

- (Step 6 & 7) Once the rest have finished the writes or errored, they report back to the primary, the primary then reports back to the client

- In case of an error, the state is left inconsistent, and the client typically retries.

Below is the flow diagram attached in the original paper, I found it pretty useful.

Is a chunkserver the primary for a file across all clients?

If not, when it tells secondaries to write data at a particular offset, couldnt it be overwriting on another primary? I’m guessing the chunk version sets would make sure the chuckserver with stale data wouldn’t be allowed to be primary, hence preventing that problem. Or if so, wouldn’t is be a bottleneck? Edit: Only one client can modify a chunk at a time

Snapshots

- Before the master creates a snapshot, it revokes the lease on chunks in files it’s going to snapshot, so that the client HAS to contact it before doing anything.

- Then it duplicates the filename, pointing the second to the same chunks. When a client does request a chunk after, it notices that the chunk is pointed to by two files, so it requests that these chucks be duplicated at that server, after which a lease is granted on the new chunk.

Replication

- Each chunk is replicated on multiple servers for high fault tolerance and replication. The usual replication number is 3.

Garbage Collection

- When a file is deleted, the mapping is removed from filename to chunk. Then during periodic scans, the master is able to identify chunks without file references, and make sure they are deleted.

High Availability

- Not are only are the chunks replicated, the metadata is replicated on servers known as shadow masters. These can be made available immediately in case of a master failure.

Neither the clients or the servers cache the data.

- Clients- have working sets too large to be cached.

- Servers- chunks are stored as local files and so Linux’s buffer cache already keeps frequently accessed data in memory.